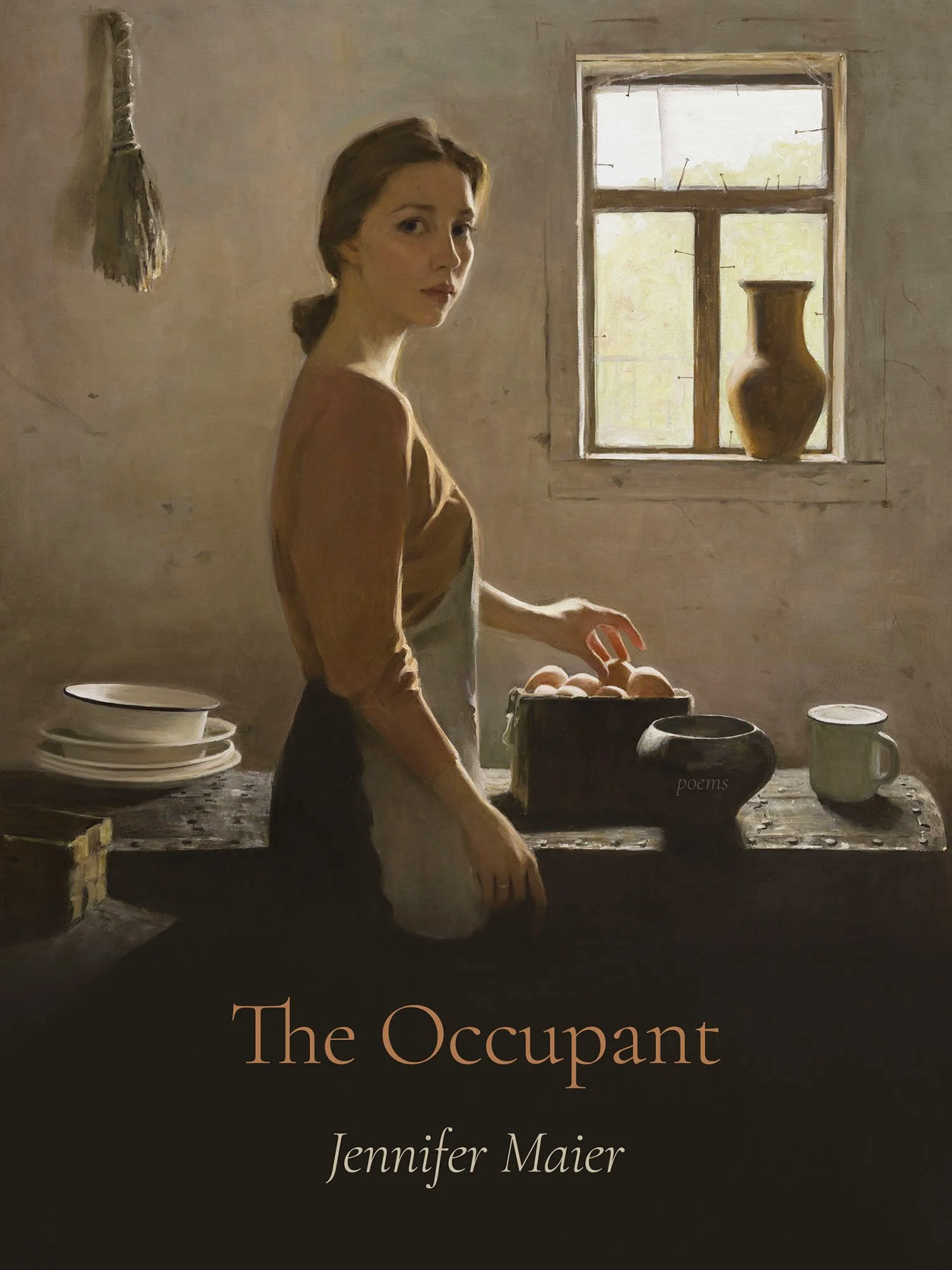

The Occupant (2025)

Pitt Poetry Series, 2025

The Occupant is a collection of persona and prose poems that explores the “inner lives” of common household objects, along with that of “The Occupant” of the house, their human keeper. Taken together, their shifting perspectives engage questions of time, mortality, and the nature of consciousness itself, reminding readers of the beauty and strangeness that lurk under the surface of ordinary thought—the “other world” that, as Paul Éluard noted, “resides in this one.”

The Author reading “The Occupant Imagines the House as a Great Fish”

Maggie Smith, “The Slowdown” (nationally syndicated podcast, Nov. 2025)

BUY NOW from University of Pittsburgh Press, Bookshop.org, and Amazon.

Reviews:

None of the great poets of the life of things, Francis Ponge, Pablo Neruda, Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, as I recall, wonder if their regard for things is proper or ethical or distorting. . . . Here, Maier reminds us that we are objects possessed by an even larger object. The Occupant is one of those rare books that can change the way we look at things and at ourselves.

— Mark Jarman, The Hudson Review

From the moment I began to read, these poems took my breath away—or quieted it, so I could hear the voices of the various objects that speak, as individual flowers do in Louise Glück’s The Wild Iris—a conch shell, a whisk, matches, lingerie. The Occupant’s enchantment is also the reader’s.

— Sharon Bryan, author of Sharp Stars

This is what makes The Occupant unique—these are not [simply] clever poems about these objects, but rather poems that allow them to reveal the occupant’s character, raise essential questions about time and beauty and how ‘we light’ our lives to keep darkness at bay. This is a mature, intelligent, and technically deft book of poems. It is an absolute pleasure to read.

— Robert Cording, author of Without My Asking

I want to call this book magical, and it is, but it's the magic of the everyday, of the aliveness and attention that flow into and through us when we can turn ourselves to meet them. Which, thankfully, Maier does, finding over and over that the things of this world are telling us everything we most need to hear.

— Kasey Jueds, author of The Thicket

-

The Occupant of Jennifer Maier’s title imagines her residence, haunted by its previous owners, to be a great fish that enfolds her and her living objects. Even her sleepwear, in the poem “Lingerie,” joins her as “morning and evening, we slide / into light— // sheer tentacles of stockings / black cuttlefish of negligee.” A matchbook, a mirror, a toothbrush, a hairbrush, a light bulb make hers a family of animated things. The imagery though it does not convey the horror imagined by Catherine Deneuve in Repulsion, nor the sublime silliness of Disney’s

Fantasia, nevertheless leads the Occupant to consider her own sanity, albeit marked by a sense of herself as an object, “still usable, able to hold nearly as much as before.” The distance between reader and description, however vivid, appears safe, set in lines of verse of the variety we have come to expect, apparent form to organize the otherwise formlessness of free verse. But when verse gives way to prose, as it does in the book’s most striking poem, “The Occupant Is Visited by the Dead Poet,” the convergence of subject and object gives off sparks.

Has the Occupant appropriated the poet by buying his book or has the poet occupied her with his poems? As time passes, and the two are “living together,” the Occupant finds “his beautiful words all over the place, on top of her own things.” Ultimately she asks, “Is this what you do now, pick up women in bookstores?” Since the objectification of the other is a central concern of modern relationships, as they are represented even in poems, we find ourselves in a fraught allegorical dimension, which makes some of the more whimsical poems, about a bowl of cherries or a dust bunny, stand as reproaches to what we might expect as readers.

None of the great poets of the life of things, Francis Ponge, Pablo Neruda, Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, as I recall, wonder if their regard for things is proper or ethical or distorting. Maier imagines returning each thing with “a note of thanks,” “Back to bone and silica the china; this silk to the mulberry leaf / Each forged thing to its atomic weight, its elemental body.” I want to say with this book that we are in the presence of a cunning critique of capitalism, ownership, with a wit that transcends Marxism. But it is the poet’s role to remind us that even that politically astute view has to be temporary, for “the Occupant looks up from her writing to trace particles of dust drifting everywhere in air, alighting on every surface.” We are objects possessed by an even larger object. The Occupant is one of those rare books that can change the way we look at things and at ourselves.

-

In Jennifer Maier’s newest collection of poetry, The Occupant, she masters the art of animating inanimate objects—a conch shell, hairbrush, even a glass of wine—and establishes an immediate emotional connection that encourages a closer examination of the community that inhabits a home. Maier probes the unique personalities of household items as the emotional journey of the Occupant who resides alongside them unfolds.

The book’s poetic structure, with its mix of prose poems, free verse, and rhymed poetry, keeps the narrator’s and objects’ voices separate, allowing for individual character refinement. The Occupant, as the individual in the house, appears within the collection’s prose poems, setting it apart from the other objects. This person is without name, referred to in the third person as “she” and “woman.” The objects flourish in traditional poetic forms as inanimate items that take center stage with first-person narration, sharing life perspectives and lessons learned, a technique successful through direct communication with the Occupant, addressing her with “you.”

Maier allows scrutiny of each object to create distinctive personalities and attitudes. For example, in poem “Matchbook,” there exists the “content of the world: / hazard and illumination— / desire, consummation, ash” as the “twenty redheaded soldiers” use fire to ignite “the candle on your birthday cake” and expand figuratively as “one to burn your bridges.” The objects also objectify the Occupant, making their observations of her actions known. In “Spider,” as the eight-legged creature considers the lacewing approaching its web, it also comments on the human counterpart in the room:

-

How would you feel upon discovering the objects of your daily, habitual use—ordinary objects of every imaginable function and variety—were inspirited, sensitively keen observers with their own desires, gripes, preoccupations, and ways of understanding the world?

This is precisely the brain-tickling puzzle Jennifer Maier’s newly-released third collection The Occupant (University of Pittsburgh Press) shakes, opens, and pieces together with feeling and skill. A deft mingling of prose and traditional poems offer pathos, wit, and vulnerable, costly wisdom as 30-odd objects speak from the vantage point of their respective individual existences alongside the titular “occupant,” – an unnamed woman living alone to whom they belong; and whose point of view is also poetically inhabited.

Maier is at her best in these moving poems, which deliberately rely on the rhythms of one person’s quotidian existence and ‘stuff’ to raise urgent, profound questions about human life and experience. Take, for instance, the goosebump-inducing rebuke of “Alarm Clock” –

How like you not to see

that even I, untouched by time, can’t keep it.

Some days I want to drop my hands

in futility at the way you equate passing with

dissolution: each tick a small erasure,

like the beat of your own heart: one less,

one less. And have you ever stopped to think

not even you can spend a thing you can’t possess?

The wonderful tonal panoply of this collection—which moves with the poet’s characteristically fluid grace through everything from wry humor (Think opposites attract?//Ix-nay on that) to loneliness (The woman wonders if she has taken up knitting because she has no children) to existential angst—is enabled by the dynamic marriage of Maier’s own prolific emotive range with the metaphysical conceit at play throughout The Occupant; which includes in its opening pages Paul Éluard’s words—“There is another world, but it is in this one” –a marvelous and discreet key unlocking the pages that follow.

In penning this review, I found I couldn’t waste my privileged position as Jennifer Maier’s MFA student-advisee. She was good enough to tell me (following the careful consideration with which she approaches even the smallest endeavor) what inanimate object she would herself elect to become for eternity. (I told her I’d be a gargoyle, which is accurate, if mildly out-of-pocket) She went with a rather more elegant selection—

‘As ever, I would be torn between beauty (my French Empire walnut bookcase) and utility (a whisk, or a pair of scissors). But if I had to be a single object for eternity, I think I would be a mirror – a beautiful one, to be sure. As a mirror, I could encounter a wide variety of faces and objects and reflect them back, neutrally, without preconceptions. And I would certainly enjoy observing the private responses—satisfaction, dismay–of those searching my reaches for “what they really are,” or believe themselves to be.’

Because of the immense and obvious thematic consistency, I wondered if Jennifer had encountered a recent, fascinating-if-head-scratching development in philosophy. I shot her an email:

Are you familiar with the (quite new!!) trend in metaphysics called Object-oriented Ontology?? There’s SO much natural overlap with your book that I think I’ll have to highlight the connection.

In brief:

Object-oriented ontology maintains that objects exist independently of human perception and are not ontologically exhausted by their relations with humans or other objects. For object-oriented ontologists, all relations, including those between nonhumans, distort their related objects in the same basic manner as human consciousness and exist on an equal ontological footing with one another.

She replied—

I was not aware per se of Object-oriented Ontology, but the objects in my home – or in the Occupant’s, for that matter – may well be “ontologically exhausted,”

especially today, when I’m trying to get everything back in order after last week’s renovations and painting (I decided to do the same color in the living room—Farrow & Ball’s “Elephant’s Breath,” partly for the name, and partly because I love how it slouches between gray and lavender, depending on light and time of day)

Ontological exhaustion is no joke—person or saucer or spider—and the remedies seem few and far between. Even so, The Occupant’s occupant appears to find a strange, imprecise respite in Maier’s closing poem; in the character of the light, which may be instructive for us all:

– Time is flowing forward again; sunlight gilding

this still room in the house of the mind that deplores a vacancy as, then and

now, the Occupant looks up from her writing to trace particles of dust drifting

everywhere in the air, alighting on every surface.